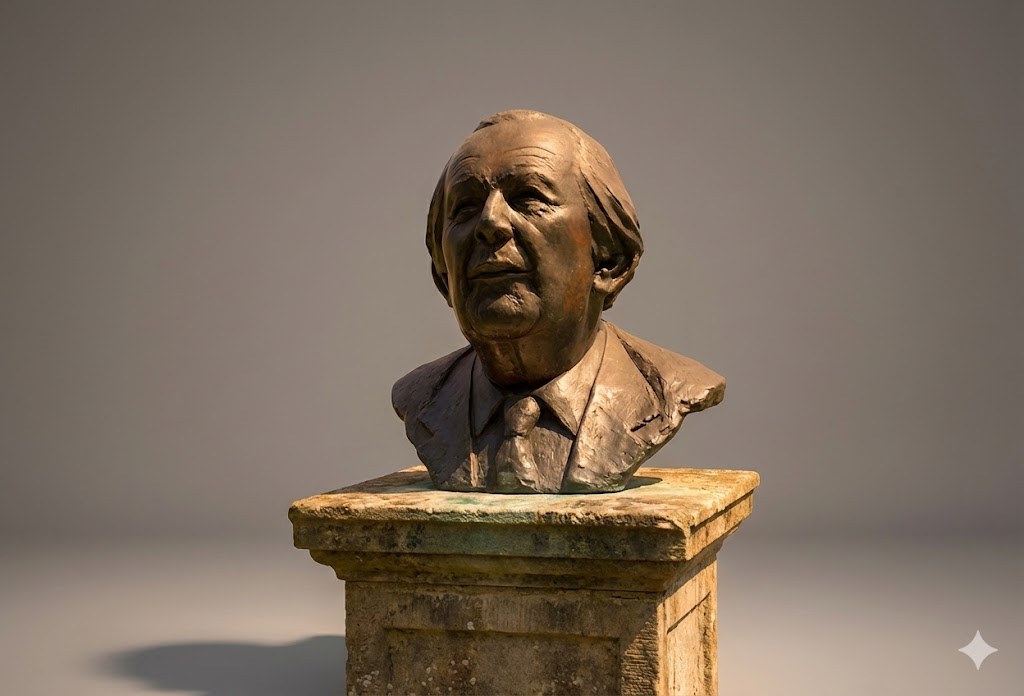

Seymour Papert looks at the work of the pioneering Swiss philosopher and psychologist

Jean Piaget spent much of his professional life listening to children, watching children and poring over reports of researchers around the world who were doing the same. He found, to put it most succinctly, that children don't think like grown-ups. After thousands of interactions with young people often barely old enough to talk, Piaget began to suspect that behind their cute and seemingly irrational utterances were thought processes that had their own kind of order and their own special logic. Einstein called it a discovery 'so simple that only a genius could have thought of it.'

Although not an educational reformer, Piaget championed a way of thinking about children that provided the foundation for today's education-reform movements. It was a shift comparable to the way modern anthropology displaced stories of primitive tribes being 'noble savages' and 'cannibals'. One might say that Piaget was the first to take children's thinking seriously.

He has been revered by generations of teachers inspired by the belief that children are not empty vessels to be filled with knowledge (as traditional pedagogical theory had it) but active builders of knowledge - little scientists who are constantly creating and testing their own hypotheses about the world. And though he may not be as famous as Sigmund Freud or even B F Skinner, his influence on psychology may be longer lasting.

In 1920, while doing research in a child-psychology laboratory in Paris, Piaget noticed that children of the same age made similar errors on intelligence tests. Fascinated by their reasoning processes, he began to suspect that the key to human knowledge might be discovered by observing how the child's mind develops. On his return to Switzerland he began watching children play, scrupulously recording their words and actions as their minds raced to find reasons for why things are the way they are.

In one of his most famous experiments, Piaget asked children, 'What makes the wind?'. A typical dialogue would be:

- Piaget: What makes the wind?

- Julia: The trees.

- Piaget: How do you know?

- Julia: I saw them waving their arms.

- Piaget: How does that make the wind?

- Julia: (waving her hand in front of his face): Like this. Only they are bigger. And there are lots of trees.

Piaget recognized that five-year-old Julia's beliefs, while not correct by any adult criterion, are not 'incorrect' either. They are entirely sensible and coherent within the framework of the child's way of knowing. Classifying them as 'true' or 'false' misses the point and shows a lack of respect for the child. What Piaget was after was a theory that the wind dialogue demonstrates coherence, ingenuity and the practice of a kind of explanatory principle (in this case by referring to body actions) that stands young children in very good stead when they don't know enough or don't have enough skill to handle the kind of explanation that grown-ups prefer.

Piaget was not an educator and never laid down rules about how to intervene in such situations. But his work strongly suggests that the automatic reaction of putting the child right may well be counter-productive. If their theories are always greeted by 'Nice try, but this is how it really is...', they might give up after a while on making theories. As Piaget put it, 'children have real understanding only of that which they invent themselves, and each time that we try to teach them something too quickly, we keep them from inventing it themselves.'

Disciples of Piaget have a tolerance for - indeed a fascination with - children's primitive laws of physics: that things disappear when they are out of sight; that the moon and the sun follow you around; that big things float and small things sink. Einstein was intrigued by Piaget's findings, especially by the idea that seven-year-olds insist that going faster can take more time - perhaps because this, like Einstein's own theories of relativity, runs so contrary to common sense.

Although every teacher in training still memorises Piaget's successive stages of childhood development, the greater part of Piaget's work is less well known, perhaps because schools of education regard it as 'too deep' for teachers. Piaget never thought of himself as a child psychologist. His real interest was epistemology - the theory of knowledge - which, like physics, was considered a branch of philosophy until Piaget came along and made it a science.

Through epistemology, Piaget explored multiple ways of knowing. He acknowledged them and examined them non-judgementally, yet with a philosopher's analytic rigour. Since Piaget, the territory has been widely colonised by those who write about women's ways of knowing, Afrocentric ways of knowing, even the computer's ways of knowing. Indeed, artificial intelligence and the information-processing model of the mind owe more to Piaget than its proponents may realise.

The core of Piaget is his belief that looking carefully at how knowledge develops in children will elucidate the nature of knowledge in general. Whether this has in fact led to deeper understanding remains, like everything about Piaget, controversial. In the past decade, Piaget has been vigorously challenged by the current fashion of viewing knowledge as an intrinsic property of the brain. Ingenious experiments have demonstrated that newborn infants already have some of the knowledge that Piaget believed children constructed. But for those, like me, who still see Piaget as the giant in the field of cognitive theory, the difference between what the baby brings and what the adult has is so immense that the new discoveries do not significantly reduce the gap, but only increase the mystery.