How much of the world around you do you really see?

Picture the following and prepare to be amazed. You're walking across a college campus when a stranger asks you for directions. While you're talking to him, two men pass between you carrying a wooden door. You feel a moment’s irritation, but you carry on describing the route. When you’ve finished, you're told you've just taken part in a psychology experiment. ‘Did you notice anything after the two men passed with the door?’ the stranger asks. ‘No,’ you reply uneasily. He explains that the man who initially approached you walked off behind the door leaving him in his place. The first man now rejoins you. Comparing them, you notice that they are of different height and build and are dressed very differently.

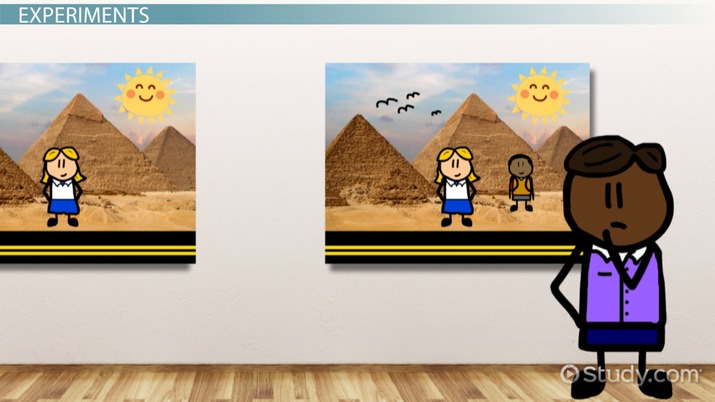

Daniel Simons of Harvard University found that 50% of participants missed the substitution because of what is called ‘change blindness’. When considered with a large number of recent experimental results, this phenomenon suggests we ‘see’ far less than we think we do. Rather than logging every detail of the visual scene, says Simons, we are actually highly selective. Our impression of seeing everything is just that. In fact, we extract a few details and rely on memory, or even our imagination, for the rest.

Until recently, scientists believed that vision involved creating images within the brain. By forming detailed internal representations of our surroundings and comparing them over time, we could detect any alterations. However, in his book Consciousness Explained, philosopher Daniel Dennett argued that our brains only store a few key details about the world, which is why we can function effectively. According to Dennett, creating elaborate images in short-term memory would consume valuable cognitive resources. Instead, we record what has changed and assume everything else remains unchanged. As a result, we inevitably overlook some details. Experiments had demonstrated that we tend to ignore elements in our visual field that seem unimportant, such as a repeated word or line in a text. But even Dennett didn’t fully realize just how little we actually ‘see.’

A year later, John Grimes from the University of Illinois drew attention by showing that people who were presented with computer-generated images of natural scenes failed to notice changes made while their eyes were, for example, scanning the scene or blinking. Dennett was pleased: ‘In hindsight, I wish I had been bolder, as the effects are more pronounced than I originally claimed.’ Subsequently, it was discovered that our eyes don’t even need to be moving to be deceived. A typical laboratory experiment might display an image on a computer screen, like a couple dining on a terrace. The image would briefly disappear, replaced by a blank screen, then reappear with a significant change, such as a raised railing behind the couple. Many people search the screen for up to a minute before spotting the alteration, and some never see it.

This is disconcerting. However, ‘change blindness’ is somewhat artificial because, in real-life scenarios, a visible motion usually signals a change. Yet, not always. As Simons points out, “We all know the experience of missing a traffic signal change because we briefly looked away. ‘Inattentional blindness’ refers to not noticing a feature of a scene when you aren’t paying attention to it.”

Last year, Simons showed people a video of a basketball game and asked them to count the passes made by one of the teams. After 45 seconds, a man in a gorilla suit slowly walked behind the players. Forty percent didn’t notice him. When the tape was replayed, and they were simply told to watch it, they easily saw the gorilla. Some even doubted it was the same video.

Now, consider if the viewers had been driving a car, and the man in the gorilla suit had been a pedestrian. Some estimates suggest that nearly half of all fatal motor vehicle accidents in the US result from driver error, including attention lapses. It's more than just academic interest that has spurred research into these cognitive errors.

These errors prompt critical questions: how can we reconcile such significant lapses with our subjective experience of continuously perceiving a rich visual environment? Last year, Stephen Kosslyn from Harvard University demonstrated that imagining a scene activates parts of the visual cortex similarly to actually seeing it. He argues that this supports the idea that we only absorb the information we consider important and mentally fill in the gaps where details are less crucial. 'The illusion that we see 'everything' is partly due to filling in gaps with memory,' he says. 'These memories can be shaped by beliefs and expectations.'

Ronald Rensink from the University of British Columbia in Canada believes our perception of a detailed visual world comes from constructing internal representations. He suggests that the brain first creates a temporary layout of the visual scene, and then our attention enhances the resolution of the scene. “What attention does,” he explains, “is stabilize these representations so they form distinct objects. Once attention shifts, they revert to an unstable, unresolved state.”

While Rensink or Kosslyn propose that internal images or memory play some role, others argue that we can perceive visual richness without storing any of that richness in our brains. Kevin O’Regan, an experimental psychologist, contends that our brains do not store a visual image of the world. Instead, we rely on the external visual environment as different parts of a scene become relevant.

According to O’Regan, our sense of controlling what we see is also an illusion. “We believe that when something flickers outside the window, we choose to look,” says Susan Blackmore from the University of the West of England, who supports O’Regan’s view. “In reality,” she explains, “our change detection mechanisms automatically drag our attention to various stimuli.”